Upon the Death of My Brother

Author: Tatiana Hensley

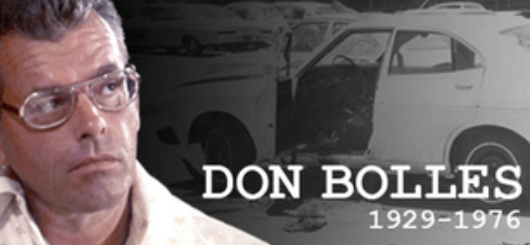

Bolles: Cautious man, dedicated journalist

Don Bolles was a cautious man.

For years, he would place a piece of Scotch tape on the hood of his car when he left it, just to be sure no one tampered with the engine. Bolles eventually got tired of the tape, and in any event, it wouldn’t have helped him detect the bomb that was fastened under his car on the day he was killed in 1976.

It was one of the ironies of his life that Bolles, the careful reporter who was rarely fooled by anyone was unprepared for what was awaiting him at a downtown Phoenix hotel on the day of the attack. But it’s only one of many ironies.

Thirty years after his death, the picture that emerges of Bolles is a contradictory one: A man who friends say valued family above all else, but who often had little time for seven children and two marriages; a great investigative reporter whose real goal was to write humor columns; the down-home Arizona newspaperman without a single national award to his name who became an icon of courage to a nation of journalists.

Bolles is one of only a handful of American journalists who have been attacked and killed in this country in retaliation for their work. His death prompted the first and only investigation by journalists coming together from all over the country in a single show of support and unity.

And next year, the Bolles’ saga will take center stage at the newly reopened Newseum in Washington, D.C., a museum honoring the work of journalists. “Bolles’ case is one of the most well-known cases of a journalist in this country paying the ultimate sacrifice -- and that is paying with his life to pursue the truth,” said Susan Bennett, the Newseum’s director of international exhibits.

While the exhibit, which will feature a video about Bolles’ and the remnants of his car, will serve to further cement Don Bolles’ place in journalism history, it does not answer one question that has been largely neglected over the past 30 years: Who was Don Bolles?

In his father’s footsteps

Bolles grew up in Teaneck, N.J., a suburban town just northwest of New York City, with his older brother, Richard, and a younger sister, Ann.

He got an early glimpse of newspapering from his father, [also named Don] chief of the Associated Press bureau in New York City.

Richard Bolles described his brother as “super, super smart,” the kind of guy who wasn’t afraid of mental or physical challenges.

“In our teens he loved to wrestle and pin me to the floor in any impulsive moment,” Richard Bolles said in an e-mail interview. “After I entered the U.S. Navy and was put in fighting trim, he tried that only once and never tried it again.”

The two brothers were as unlike as two people could be, Richard Bolles said. “He was dead serious; I was very playful. He was very left-brained; I was very right-brained. He was courageous in the face of danger and death; I never was.”

Don Bolles went to Beloit College, Wis., where he became editor of the college newspaper and won a President’s Award for personal achievement, according to newspaper articles written about him.

After graduating from college in 1950 with a degree in government, Bolles joined the Army and was sent to Korea, where he was assigned to an anti-aircraft unit, according to the news reports. In 1953 Bolles followed his father to the Associated Press, working as a sports editor and rewrite man in New York, New Jersey and Kentucky.

Bolles’ mission quickly became to “expose wrongdoing,” his brother said. “He traveled all over the United States, sometimes incognito and with false papers, in order to track down wrong-doers, including the mafia, state water commissioners and state tax commissioners.”

In 1962, Bolles landed a job as a reporter at The Arizona Republic and immediately began making a name for himself. He probed the influence of the mafia on Arizona dog and horse racing, uncovered bribery and kickbacks on the state tax and corporation commissions, investigated a conflict-of-interest scandal involving two state legislators and exposed swindles involving the sale of Arizona land to people across the country. In 1974, he was named Arizona Press Club Newsman of the Year.

Bolles’ colleagues considered him a superb digger. Bob Early, the Republic’s city editor at the time, said, “Wherever he went, he ran into very good stories, usually scandals or crimes of some kind… He was always looking into problems and trying to expose wrongdoing.”

“You could not ask for better” from a reporter, Early added. “He was always working; I do not think he took time off. He worked really hard.”

Former Republic reporter Paul Dean, one of Bolles’ best friends, said he remembers working with Bolles on a story involving the Arizona Highway Patrol. The two of them went down to interview the superintendent. Bolles had a file in his lap and every once in a while, he would open the file, look at it, then close it and ask another question.

“After a half an hour of this, the poor guy wouldn’t dare lie because he knew Bolles had something in the file,” Dean said. “But Bolles only had blank papers. It worked terrifically.”

He and another reporter put together a list of nearly 200 known mafia members allegedly operating in the state and named them in a story, along with their business associates. His data base was a pack of 3-by-5 index cards with information on every known and suspected organized crime figure in Arizona and their associates.

It was his stories exposing the mafia, officials believe, that turned him into a target.

Bolles had his phone and his bank account tapped and was getting death threats, his brother, Richard, wrote in the epilogue of his book about life and work planning, which was dedicated to “reporter, hero, and beloved brother.”

They could threaten Bolles, “but they could not take away his passion for truth, his hatred of corruption, his integrity, his courage, nor his love,” Richard Bolles wrote.

A dark humor

Bolles loved his work, but what he really wanted was to write a humor column.

“Once every two or three weeks, Bolles would turn in a humor column, but it never got published,” Early said. “He did not have the knack for it.” The closest he came was writing several humor sketches that were performed at the annual state Gridiron show, a gathering of journalists and politicians.

Charles Kelly, who was a young reporter at the Republic at the time, said Bolles was known as a great reporter but not a gifted writer. “His leads always had to be rewritten because he put soft leads on hard news stories,” Kelly said.

Kelly and others remember Bolles as a tall man with a nasally voice who liked to smoke a pipe. He favored aviator sunglasses, leisure suits and white shoes. He was invariably cheerful and optimistic, even though he described himself as a cynic. Photos from the time show him with dark-rimmed glasses and a slight pompadour – out of fashion even then.

Dean, who was best man at Bolles’ second wedding, said it is Bolles’ laugh that has stuck with him all these years.

“I can still hear it to this day,” he said. “Very few people can throw their head back and laugh.”

He had a dark sense of humor and sometimes joked about his own death. According to Kelly, Bolles once told a colleague, ‘If something bad happens to me, save what’s left for the chili.’”

He grew ever more cautious. He would meet sources only in public places, Kelly said. He asked questions first and trusted later.

George Weisz, who later led an investigation into Bolles’ murder, was a student at the University of Arizona at the time, researching organized crime. He contacted Bolles and they talked several times on the phone, but not before Bolles got a letter from Weisz’ professor verifying that Wesz was who he claimed to be. “Don was cautious that way,” Weiz wrote in tribute to Bolles five years ago.

Bolles was not the kind of guy who liked to talk about cars or play golf, friends and colleagues said. His life revolved mostly around work. But he also found time for drinking and a certain amount of carousing; Dean described him as a “ladies’ man.”

After his first marriage fell apart, Bolles moved in with Dean at 1217 N. Third Street. It was a complex where a lot of other journalists lived, and the place was a typical bachelor’s apartment, bed in one corner, refrigerator in the other.

On Friday nights, they would throw parties for other journalists, sources and community leaders.

“We shared enough tables in enough bars,” Dean said. “We had that kind of friendship.”

But then Bolles met Rosalie Kasse, and on June 2, 1968, the two married in a small ceremony at a church on Third Street and McDowell in Phoenix. Bolles had four children from his first marriage and Rosalie two. Together they had a daughter, who was born deaf; Bolles was said to be devoted to her.

Rosalie described her husband as a family-oriented man -- fair and tough. He loved his work, but in the months before his death, he was ready for a change, she said in a written response to questions about her husband’s life.

He “planned to focus his journalistic talents on less dangerous areas,” she wrote. “The danger caught up with him, however, and we never had a chance to have a different life together.”

Colleagues concurred, saying that Bolles seemed to grow disillusioned in late 1975 and early 1976. He indicated that he was tired of writing about corruption when no one else seemed to care, and he asked to be taken off the investigative beat. He was reassigned to Phoenix City Hall, and then to the state Legislature. “Bolles was burned out on investigative reporting,” Early said. “He had been doing it for 10 years, exposing people, and not much happened” as a result.

A hotel rendezvous

On June 2, 1976, Bolles had a routine hearing to cover at the State Capitol. It was also his eighth wedding anniversary, and he and Rosalie planned to go see a movie that night, possibly “All the Presidents’ Men,” about the investigative reporters who broke the Watergate story that brought down Richard Nixon’s presidency.

Bolles drove to the Hotel Clarendon in downtown Phoenix to meet a man who promised him information about a land deal involving top state politicians, according to news reports of the time. He left a note in his typewriter at the office saying he would meet with the informant, then go to a luncheon meeting and be back about 1:30 p.m.

He walked into the hotel lobby and had been waiting for a few minutes when a call came to the desk for him. He spoke on the phone for a minute or two then left the hotel, according to the reports. His car was in the parking lot just to the south of the hotel on Fourth Avenue.

He apparently started the car and had moved a few feet when a bomb strapped to the underside of the car detonated, blowing open the driver’s door and shattering his lower body.

Back in the newsroom

Dean was in the newsroom working on his column that morning when police reporter Jack West heard something on the police scanner about an explosion at the Clarendon, a white car and a reporter.

Early, who was working the city desk that day, said his first thought was that it was Al Sitter, who was on the investigative beat at the time and drove a white Toyota. About five minutes later, Sitter walked in the door of the newsroom and Early shouted, “You’re alive?” Sitter answered, “Why wouldn’t I be?”

Dean remembered that everybody in the newsroom started yelling and screaming, “What was Bolles doing today? What was he working on? What was he on?”

Early got on the phone with the Department of Motor Vehicles, which confirmed that the car that had been bombed belonged to Bolles. He hung up the phone and hit the desk. “Jesus Christ,” he screamed. Dean had a cup of coffee in his hand and he threw it against the wall.

“All of a sudden anger, rage, resentment and frustration swept around the newsroom,” Dean said. Dean headed to the Clarendon to cover the story and then to St. Joseph’s Hospital. “When I saw Bolles, I almost did not recognize him, with all the tubes coming out of him and plugged into the wall,” he said. He wondered if Bolles knew what happened, if he felt the pain. He hoped not.

Early said “The toughest was how he died. It was a brutal and horrible way to go.”

At the Republic, everyone was scrambling to report the story. It was hard to convince reporters to go home long enough to change clothes, Dean said.

Early said no one wanted to do anything but find out what had happened to Bolles. “It was difficult to keep the staff doing what they were supposed to be doing,” he said.

Richard Bolles recalled that he “cried buckets” when he heard the news “As he was my younger brother, I always thought that some day he would stand at my gravesite. I never dreamed that I would stand at his.”

An ordinary guy

Thirty years later, Bolles the man has largely become Bolles the legend, but it’s a legacy that family and friends embrace.

“Bolles was a perfect example of why there are constitutional protections for freedom of press,” Early said. “When the founding fathers developed the Constitution and the Bill of Rights, they had in mind that a free press would be the watchdog of the government.

Watchdogs like Bolles.

“Bolles raised the bar for investigative reporting, and I often wonder with computers and the internet, what would Bolles have done with that?” Dean said.

According to Dean, Bolles would be proud of his place in journalism history, but he would be surprised by the acclaim.

“Bolles would be rolling his eyes, saying, ‘Me?’ He recognized his flaws, his talents, his limitations,” Dean said.

His brother said Bolles would view all the admiration with typical wry skepticism.

Dean concurred. “He would be saying, ‘Do I deserve this?’ As a journalist he would be a little ashamed of this martyrdom. He has become a white knight in a shining armor but he would say, ‘This is not me, and it will never be me. I’m just an ordinary guy.’”

For years, he would place a piece of Scotch tape on the hood of his car when he left it, just to be sure no one tampered with the engine. Bolles eventually got tired of the tape, and in any event, it wouldn’t have helped him detect the bomb that was fastened under his car on the day he was killed in 1976.

It was one of the ironies of his life that Bolles, the careful reporter who was rarely fooled by anyone was unprepared for what was awaiting him at a downtown Phoenix hotel on the day of the attack. But it’s only one of many ironies.

Thirty years after his death, the picture that emerges of Bolles is a contradictory one: A man who friends say valued family above all else, but who often had little time for seven children and two marriages; a great investigative reporter whose real goal was to write humor columns; the down-home Arizona newspaperman without a single national award to his name who became an icon of courage to a nation of journalists.

Bolles is one of only a handful of American journalists who have been attacked and killed in this country in retaliation for their work. His death prompted the first and only investigation by journalists coming together from all over the country in a single show of support and unity.

And next year, the Bolles’ saga will take center stage at the newly reopened Newseum in Washington, D.C., a museum honoring the work of journalists. “Bolles’ case is one of the most well-known cases of a journalist in this country paying the ultimate sacrifice -- and that is paying with his life to pursue the truth,” said Susan Bennett, the Newseum’s director of international exhibits.

While the exhibit, which will feature a video about Bolles’ and the remnants of his car, will serve to further cement Don Bolles’ place in journalism history, it does not answer one question that has been largely neglected over the past 30 years: Who was Don Bolles?

In his father’s footsteps

Bolles grew up in Teaneck, N.J., a suburban town just northwest of New York City, with his older brother, Richard, and a younger sister, Ann.

He got an early glimpse of newspapering from his father, [also named Don] chief of the Associated Press bureau in New York City.

Richard Bolles described his brother as “super, super smart,” the kind of guy who wasn’t afraid of mental or physical challenges.

“In our teens he loved to wrestle and pin me to the floor in any impulsive moment,” Richard Bolles said in an e-mail interview. “After I entered the U.S. Navy and was put in fighting trim, he tried that only once and never tried it again.”

The two brothers were as unlike as two people could be, Richard Bolles said. “He was dead serious; I was very playful. He was very left-brained; I was very right-brained. He was courageous in the face of danger and death; I never was.”

Don Bolles went to Beloit College, Wis., where he became editor of the college newspaper and won a President’s Award for personal achievement, according to newspaper articles written about him.

After graduating from college in 1950 with a degree in government, Bolles joined the Army and was sent to Korea, where he was assigned to an anti-aircraft unit, according to the news reports. In 1953 Bolles followed his father to the Associated Press, working as a sports editor and rewrite man in New York, New Jersey and Kentucky.

Bolles’ mission quickly became to “expose wrongdoing,” his brother said. “He traveled all over the United States, sometimes incognito and with false papers, in order to track down wrong-doers, including the mafia, state water commissioners and state tax commissioners.”

In 1962, Bolles landed a job as a reporter at The Arizona Republic and immediately began making a name for himself. He probed the influence of the mafia on Arizona dog and horse racing, uncovered bribery and kickbacks on the state tax and corporation commissions, investigated a conflict-of-interest scandal involving two state legislators and exposed swindles involving the sale of Arizona land to people across the country. In 1974, he was named Arizona Press Club Newsman of the Year.

Bolles’ colleagues considered him a superb digger. Bob Early, the Republic’s city editor at the time, said, “Wherever he went, he ran into very good stories, usually scandals or crimes of some kind… He was always looking into problems and trying to expose wrongdoing.”

“You could not ask for better” from a reporter, Early added. “He was always working; I do not think he took time off. He worked really hard.”

Former Republic reporter Paul Dean, one of Bolles’ best friends, said he remembers working with Bolles on a story involving the Arizona Highway Patrol. The two of them went down to interview the superintendent. Bolles had a file in his lap and every once in a while, he would open the file, look at it, then close it and ask another question.

“After a half an hour of this, the poor guy wouldn’t dare lie because he knew Bolles had something in the file,” Dean said. “But Bolles only had blank papers. It worked terrifically.”

He and another reporter put together a list of nearly 200 known mafia members allegedly operating in the state and named them in a story, along with their business associates. His data base was a pack of 3-by-5 index cards with information on every known and suspected organized crime figure in Arizona and their associates.

It was his stories exposing the mafia, officials believe, that turned him into a target.

Bolles had his phone and his bank account tapped and was getting death threats, his brother, Richard, wrote in the epilogue of his book about life and work planning, which was dedicated to “reporter, hero, and beloved brother.”

They could threaten Bolles, “but they could not take away his passion for truth, his hatred of corruption, his integrity, his courage, nor his love,” Richard Bolles wrote.

A dark humor

Bolles loved his work, but what he really wanted was to write a humor column.

“Once every two or three weeks, Bolles would turn in a humor column, but it never got published,” Early said. “He did not have the knack for it.” The closest he came was writing several humor sketches that were performed at the annual state Gridiron show, a gathering of journalists and politicians.

Charles Kelly, who was a young reporter at the Republic at the time, said Bolles was known as a great reporter but not a gifted writer. “His leads always had to be rewritten because he put soft leads on hard news stories,” Kelly said.

Kelly and others remember Bolles as a tall man with a nasally voice who liked to smoke a pipe. He favored aviator sunglasses, leisure suits and white shoes. He was invariably cheerful and optimistic, even though he described himself as a cynic. Photos from the time show him with dark-rimmed glasses and a slight pompadour – out of fashion even then.

Dean, who was best man at Bolles’ second wedding, said it is Bolles’ laugh that has stuck with him all these years.

“I can still hear it to this day,” he said. “Very few people can throw their head back and laugh.”

He had a dark sense of humor and sometimes joked about his own death. According to Kelly, Bolles once told a colleague, ‘If something bad happens to me, save what’s left for the chili.’”

He grew ever more cautious. He would meet sources only in public places, Kelly said. He asked questions first and trusted later.

George Weisz, who later led an investigation into Bolles’ murder, was a student at the University of Arizona at the time, researching organized crime. He contacted Bolles and they talked several times on the phone, but not before Bolles got a letter from Weisz’ professor verifying that Wesz was who he claimed to be. “Don was cautious that way,” Weiz wrote in tribute to Bolles five years ago.

Bolles was not the kind of guy who liked to talk about cars or play golf, friends and colleagues said. His life revolved mostly around work. But he also found time for drinking and a certain amount of carousing; Dean described him as a “ladies’ man.”

After his first marriage fell apart, Bolles moved in with Dean at 1217 N. Third Street. It was a complex where a lot of other journalists lived, and the place was a typical bachelor’s apartment, bed in one corner, refrigerator in the other.

On Friday nights, they would throw parties for other journalists, sources and community leaders.

“We shared enough tables in enough bars,” Dean said. “We had that kind of friendship.”

But then Bolles met Rosalie Kasse, and on June 2, 1968, the two married in a small ceremony at a church on Third Street and McDowell in Phoenix. Bolles had four children from his first marriage and Rosalie two. Together they had a daughter, who was born deaf; Bolles was said to be devoted to her.

Rosalie described her husband as a family-oriented man -- fair and tough. He loved his work, but in the months before his death, he was ready for a change, she said in a written response to questions about her husband’s life.

He “planned to focus his journalistic talents on less dangerous areas,” she wrote. “The danger caught up with him, however, and we never had a chance to have a different life together.”

Colleagues concurred, saying that Bolles seemed to grow disillusioned in late 1975 and early 1976. He indicated that he was tired of writing about corruption when no one else seemed to care, and he asked to be taken off the investigative beat. He was reassigned to Phoenix City Hall, and then to the state Legislature. “Bolles was burned out on investigative reporting,” Early said. “He had been doing it for 10 years, exposing people, and not much happened” as a result.

A hotel rendezvous

On June 2, 1976, Bolles had a routine hearing to cover at the State Capitol. It was also his eighth wedding anniversary, and he and Rosalie planned to go see a movie that night, possibly “All the Presidents’ Men,” about the investigative reporters who broke the Watergate story that brought down Richard Nixon’s presidency.

Bolles drove to the Hotel Clarendon in downtown Phoenix to meet a man who promised him information about a land deal involving top state politicians, according to news reports of the time. He left a note in his typewriter at the office saying he would meet with the informant, then go to a luncheon meeting and be back about 1:30 p.m.

He walked into the hotel lobby and had been waiting for a few minutes when a call came to the desk for him. He spoke on the phone for a minute or two then left the hotel, according to the reports. His car was in the parking lot just to the south of the hotel on Fourth Avenue.

He apparently started the car and had moved a few feet when a bomb strapped to the underside of the car detonated, blowing open the driver’s door and shattering his lower body.

Back in the newsroom

Dean was in the newsroom working on his column that morning when police reporter Jack West heard something on the police scanner about an explosion at the Clarendon, a white car and a reporter.

Early, who was working the city desk that day, said his first thought was that it was Al Sitter, who was on the investigative beat at the time and drove a white Toyota. About five minutes later, Sitter walked in the door of the newsroom and Early shouted, “You’re alive?” Sitter answered, “Why wouldn’t I be?”

Dean remembered that everybody in the newsroom started yelling and screaming, “What was Bolles doing today? What was he working on? What was he on?”

Early got on the phone with the Department of Motor Vehicles, which confirmed that the car that had been bombed belonged to Bolles. He hung up the phone and hit the desk. “Jesus Christ,” he screamed. Dean had a cup of coffee in his hand and he threw it against the wall.

“All of a sudden anger, rage, resentment and frustration swept around the newsroom,” Dean said. Dean headed to the Clarendon to cover the story and then to St. Joseph’s Hospital. “When I saw Bolles, I almost did not recognize him, with all the tubes coming out of him and plugged into the wall,” he said. He wondered if Bolles knew what happened, if he felt the pain. He hoped not.

Early said “The toughest was how he died. It was a brutal and horrible way to go.”

At the Republic, everyone was scrambling to report the story. It was hard to convince reporters to go home long enough to change clothes, Dean said.

Early said no one wanted to do anything but find out what had happened to Bolles. “It was difficult to keep the staff doing what they were supposed to be doing,” he said.

Richard Bolles recalled that he “cried buckets” when he heard the news “As he was my younger brother, I always thought that some day he would stand at my gravesite. I never dreamed that I would stand at his.”

An ordinary guy

Thirty years later, Bolles the man has largely become Bolles the legend, but it’s a legacy that family and friends embrace.

“Bolles was a perfect example of why there are constitutional protections for freedom of press,” Early said. “When the founding fathers developed the Constitution and the Bill of Rights, they had in mind that a free press would be the watchdog of the government.

Watchdogs like Bolles.

“Bolles raised the bar for investigative reporting, and I often wonder with computers and the internet, what would Bolles have done with that?” Dean said.

According to Dean, Bolles would be proud of his place in journalism history, but he would be surprised by the acclaim.

“Bolles would be rolling his eyes, saying, ‘Me?’ He recognized his flaws, his talents, his limitations,” Dean said.

His brother said Bolles would view all the admiration with typical wry skepticism.

Dean concurred. “He would be saying, ‘Do I deserve this?’ As a journalist he would be a little ashamed of this martyrdom. He has become a white knight in a shining armor but he would say, ‘This is not me, and it will never be me. I’m just an ordinary guy.’”

Tatiana Hensley

Special to The Arizona Republic

May. 28, 2006